“I am constantly being pressed to take a stand on one issue after another. It is one of the biggest challenges I face on a daily basis,” lamented the president of a private university to a group of seven at a recent CEO retreat I was leading. The other CEOs jumped in, sharing their own experiences with groups who want leadership to side with them on contentious issues: critical race theory, fossil fuels, abortion, gender, COVID-19 protocols, immigration.

Of course, standing with stakeholders on one side of issues like those means incurring the wrath of those on the other side. Each group’s members think they are right and often consider themselves superior to groups with whom they have differences. The leader who takes no stand, or tries to reconcile the sides, or takes an outspoken stand often finds there is no safe or constructive place to stand.

No surprise, leadership fatigue is real. Around the country we see headlines like this one announcing resignations or retirements of 10 district superintendents of schools in North Texas — including Dallas, Fort Worth, Plano — in the past four months.

Dealing with differences: four levels of group functioning

Based on my 20 years as a CEO, my work with scores of for-profit and nonprofit leaders and the extensive reservoir of social science data available, I see four stage of group conflict: differences, division, polarization and demonization.

Each level has distinct identifiable behaviors. They define how we treat one another and the type of relationship we intend, regardless of the content of the specific differences involved. These four levels can serve as a roadmap to examine and redirect the state of a marriage, a church, an advertising campaign, a political movement or even a nation. They can help us distinguish between two very different questions: Where do I stand on an issue? How will I treat those who see the issue differently?

Differences

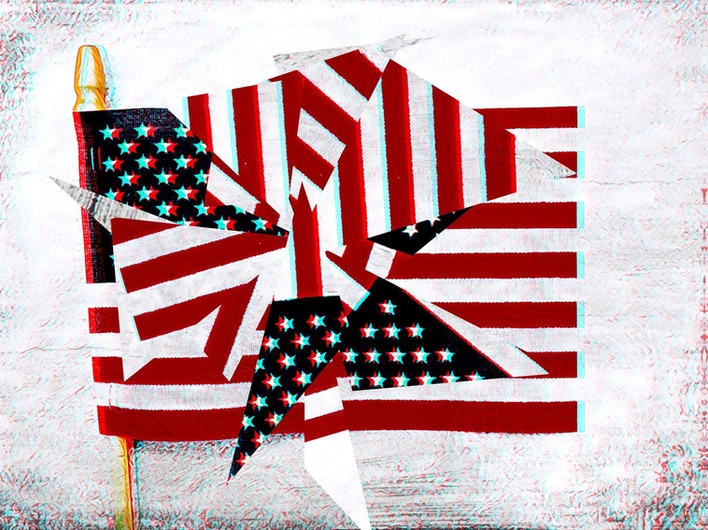

In Level 1, individual differences are present and acknowledged, but the group remains cohesive. E pluribus unum. Unity of purpose, but not uniformity of individuals.

Level 1 benefits from the constructive and innovative value of diverse voices and opinions. While differences exist, borders have not formed and there are no negatives for having relationships with others with different opinions. In Level 1, relational unity takes precedence over ideological belief, and leaders focus on keeping everyone connected.

This is an environment where seeking truth, solving problems and focusing on strategy can thrive over power-based winning of arguments. Start-ups and early-stage organizations imbued with strong purpose are more likely to exhibit Level 1 characteristics.

Division

In Level 2, subgroups form, organize and divide into camps that begin to advocate for their cause or issue. Yet, because people still interact with the group at large and with other camps, there is still a flow of information and relationships that produce insights and influence among camps. Group borders form, but they are open.

Unofficial leaders emerge in these camps. These natural leaders set the agenda for their groups, sometimes without even knowing it.

Organizational leaders in a Level 2 institution often walk on eggshells to navigate controversial issues while emphasizing higher, unifying purpose and encouraging people and groups to stay connected.

Churches, schools and nonprofits working through challenging issues like gender or race, but still hanging together, are likely in Level 2.

Polarization

Level 3 is about separation. This is where divided camps devolve into polarized tribes. It’s where relational walls are built to stop the flow of information and relationships. Distrust becomes the defining lens. Commitment to tribal belief and belonging now overtakes relationships with the whole. The border closes and the unofficial leaders of Level 2 camps become tribal power brokers who move to purify the group by embracing more extreme positions and pressing moderates to choose sides. Battles that rage inside the tribe can now become as vicious as those with opposing tribes. The ability of the larger organization to solve problems or address strategic issues just about disappears.

Married partners move into separate bedrooms and stop speaking. Opposing board members splinter the board and stop communicating. Churches split. Collaboration with the opposition is punished.

Leaders in Level 3 must then decide how to respond to the fracture, how to mitigate the destruction, when to let go.

Demonization

In Level 4 the focus shifts: separation descends into blaming, demonizing and canceling oppositional tribes. This is armies at war, energized by hatred and commitment to defeating the other side at any cost. A closed border becomes a border war. Divorcing spouses fight over property or custody.

Previously held beliefs now can be opportunistically shifted or outright reversed, no matter how hypocritical, so long as it helps destroy the other side. Think of how some evangelicals condemned President Bill Clinton on moral grounds and then supported President Donald Trump 20 years later. Or how some Democrats have reversed their opposition to the repeal of the filibuster.

The other side is blamed for whatever is bad and characterized as an existential threat. Language becomes weaponized.

Where to go from here

Reviewing these four levels, it can be easy to label the groups we’re a part of. It’s obvious, for instance, that many politically engaged Americans have descended to demonization.

But diagnosing others isn’t the most helpful use for this leadership tool; self-reflection is. Each of us is a leader somewhere. Every person reading this has influence in a family, a workplace, a classroom or a peer group. That’s where we should start. The 13th century poet Rumi said: “Yesterday I was clever so I wanted to change the world. Today I am wise, so I am changing myself.”

Strong leaders start with themselves and then influence others with that authenticity rather than authoritarian control. No matter how right or powerful you are, demonizing others will not engender sustainable change. In the words of Nelson Mandela: “There is nobody more dangerous than one who has been humiliated.”

Those seven CEOs at my retreat faced countless challenges trying to move their organizations forward in unity. They are the same challenges faced by leaders of nations, families, unions or PTOs.

The beauty of working in these relationships is that we “rub off on each other,” to use a Richard Rohr term. As the roadmap of the four levels makes clear, we have a choice: We can rub off on each other in a way that treats differences as a means to build influential relationships, or we can use our differences to destroy relationships.

N.B.: This piece is published here by permission of the author, and was originally published in The Dallas Morning News